“We were at a standstill, and if we couldn’t come up with a solution to shore up that part of the structure,” Tim Robson recalls, “we’d be sending our people into a much riskier situation. In fact, some areas were so dangerous, we had to start thinking about things like, “Who’s not married?” and “Who doesn’t have kids?” It was awful, but it was something we had to think about.”

On September 12, 2001, Tim Robson was sent to the Pentagon with his FEMA Urban Search and Rescue New Mexico Task Force 1 team. Their objectives were to search for survivors, recover victims, structurally stabilize the damaged area of the building, and locate several safes containing classified documents. Because the site was a crime scene, they also had to document and preserve key pieces of information for the FBI.

Tim’s team began their work in the rubble on the edges of the impact zone, but they quickly reached the area where the building hadn’t completely collapsed. It was inside the building where there was the highest probability of finding survivors, but it was also too dangerous to send rescuers into these overhead environments before stabilizing the structure. The building had already suffered pancake and lean-to collapses in the hours after initial impact. Extreme heat from the explosion and burning jet fuel weakened the building’s support columns. This created an extraordinarily hazardous environment for the search and rescue teams.

“The left side of the impact zone, on the outermost ring of the Pentagon – part of that wall was actually moving,” Tim recalls. “The loads were so great… any movement was very hazardous. It was definitely stressful. But we were extremely task-oriented and we wanted to get the job done and get out of there.”

The textbook approach to stabilizing a heavy building with extensive structural damage like this was to stack 6x6 timbers in a box around each damaged column. “It’s just like stacking Lincoln Logs,” explains Tim. This provides a very strong and stable support structure in case the column fails.

However, it only works if there’s something substantial overhead for the stacked timbers to support, and in the case of several weakened columns on the outer edge of the building, the ceiling didn’t exist all the way around the columns.

The team put their heads together to come up with alternative solutions and workarounds, but nobody was very comfortable with any of the ideas floated. Tim knew that the stacked timbers approach derived its strength from the joints at the corners where the timbers overlapped. With that principle in mind, Tim came up with the idea to connect two boxes of stacked timbers together by using longer timbers on one edge of each box and overlapping those longer timbers.

“I stacked some pencils together to show what I was thinking,” Tim says, “and the engineers did some quick math and said, ‘Heck yeah, let’s run with this.’ It was not something anyone on the team had ever seen before, but when we all thought about the support it would provide, it just made sense.”

This improvised solution greatly reduced the risk of the building collapsing while rescuers were inside, and the team was able to get on with their very difficult search and recovery tasks.

There are several takeaways here. Let’s never forget the courage of our search and rescue team members in the aftermath of September 11th - they willingly ventured into hazardous territory and subjected themselves to the possibility of a follow-on terrorist attack, airborne toxins, and exposure to mass carnage. For this, they have our eternal gratitude and respect.

The learning takeaway for rescuers is to deepen your knowledge. Because no two rescue situations are exactly alike, a rescuer who understands the principles (the “why”) will be much more effective than one who just memorizes procedures (the “how”). In a dynamic situation, the “textbook approach” may not offer a solution, so understanding the key principles allows you to adapt what you know to the specific situation. Creative solutions exist everywhere. This is a great example of how a thorough understanding of the principles spawned a creative solution to a difficult problem.

The learning takeaway for rescuers is to deepen your knowledge. Because no two rescue situations are exactly alike, a rescuer who understands the principles (the “why”) will be much more effective than one who just memorizes procedures (the “how”). In a dynamic situation, the “textbook approach” may not offer a solution, so understanding the key principles allows you to adapt what you know to the specific situation. Creative solutions exist everywhere. This is a great example of how a thorough understanding of the principles spawned a creative solution to a difficult problem.

After the mission was over, Tim’s creative technique became part of the operational procedures for FEMA’s search and rescue teams going forward. And ultimately, nobody was haunted by the decisions that were made about who to send into the building to do the work. Special thanks to Tim Robson and to everyone who took risks and made sacrifices to help others after September 11.

Tim Robson is a chief instructor and the New Mexico CSRT Director for Roco Rescue, Inc. As a chief instructor, he teaches a wide variety of technical rescue classes and has been instrumental in the development of our Trench & Structural Collapse Rescue programs. In his role as a CSRT Director, he leads our on-site rescue and safety services, which includes standby rescue, confined space program management, leading safety meetings and more. Prior to joining Roco in 1996, he served in the U.S. Marine Corps as a Rescue Diver/Swimmer, at the Albuquerque Fire Department, and as a Rescue Squad Officer for FEMA’s New Mexico Task Force 1.

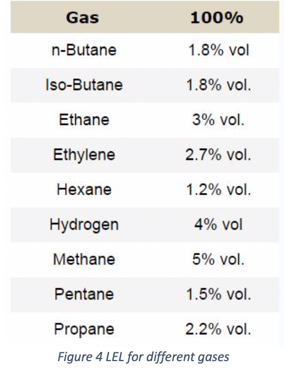

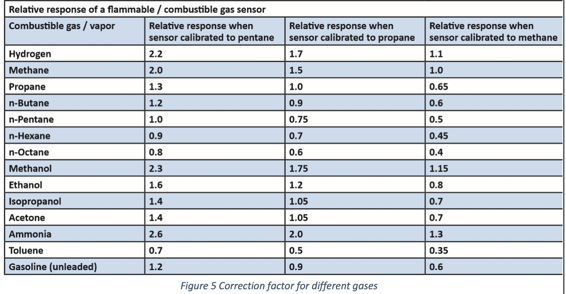

The reason pentane is sometimes used for calibration is that it overestimates the actual LEL. The caveat is that if the meter is poisoned for methane, a methane bump test is indicated.

The reason pentane is sometimes used for calibration is that it overestimates the actual LEL. The caveat is that if the meter is poisoned for methane, a methane bump test is indicated.