Tunnel Rescue in Charleston

By Skip Williams

Contributors: Deputy Chief Kenneth Jenkins, Captain Tom Horn and Captain Anthony Morley, Charleston Fire Department, Rescue 115, and Russ Fennema, Jay Dee Contractors

Note: The following article recounts a very successful rescue that took advantage of available resources at the scene. Roco Rescue wants to share stories like this one to remind our readers that lessons learned can be gleaned from successful rescues just as they can from rescues that didn’t go so well. The important point is to take the time to perform a debriefing as soon as possible after the rescue effort. This is the time to capture the thoughts and comments from the team members while it is still fresh in their memories. Any important lessons learned need to be captured through documentation and then SHARED. The learnings can become part of your SOP/SOI or they can become integrated into your formal training.

The other point that this article makes is to know and understand your equipment. We regularly train with our ropes and hardware, and we all tend to learn the operating limits and capabilities of said equipment. However, we need to be just as familiar with our peripheral equipment such as atmospheric monitors, radios, and etcetera. Consider spending some of your team training time learning more about that equipment and how to properly use it and what its idiosyncrasies may be. All the equipment we use should be considered life support equipment, and the word “life” should grab your attention and motivate you to know all you can about it.

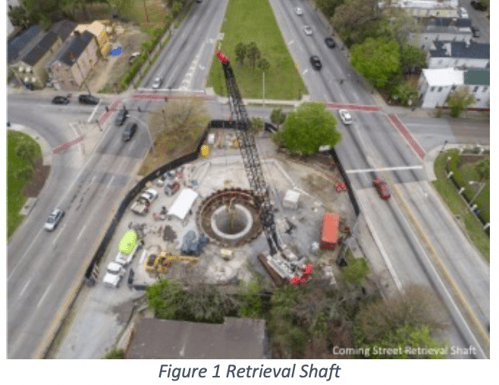

In March 2019, Rescue 115 of the Charleston Fire Department was dispatched at 09:02 hours to “man down” at an address on Shepard Street some 5 1/2 blocks NW of station 15 on Coming Street. En route, Captain Tom Horn realized the address was familiar as the entrance to the Coming Street retrieval shaft of the Charleston tunnel project (Figure 1). Now they were 2 blocks from the scene and he immediately called for Ladder 4 also from station 15, and nearby Engine 6 and Battalion 3 from nearby station 6. R115 arrived at 09:06 hours.

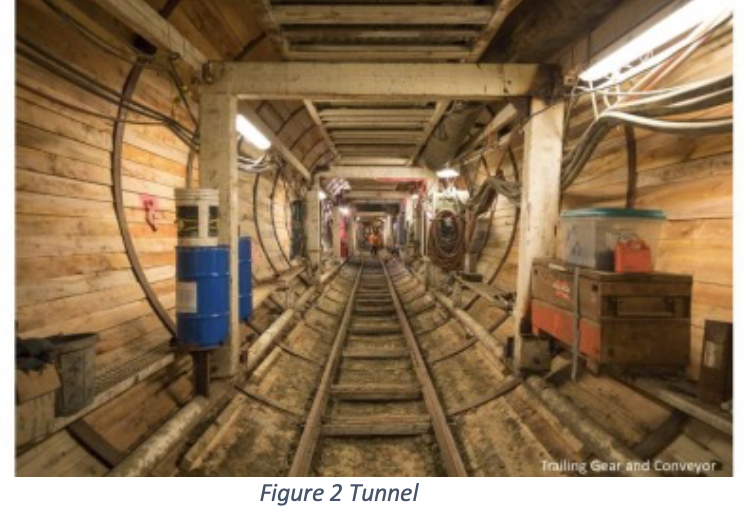

The Coming Street retrieval shaft is a vertical shaft 168 feet down and 20 feet in diameter to a 15-foot diameter tunnel being bored for flood control (Figure 2). Just as R115 arrived at the scene, the 12-man cage had been weight tested and prepared for lowering by crane. As R115’s four-man crew was about to be lowered into the shaft, Captain Horn eyed Captain of Ladder 4 and transferred command to him.

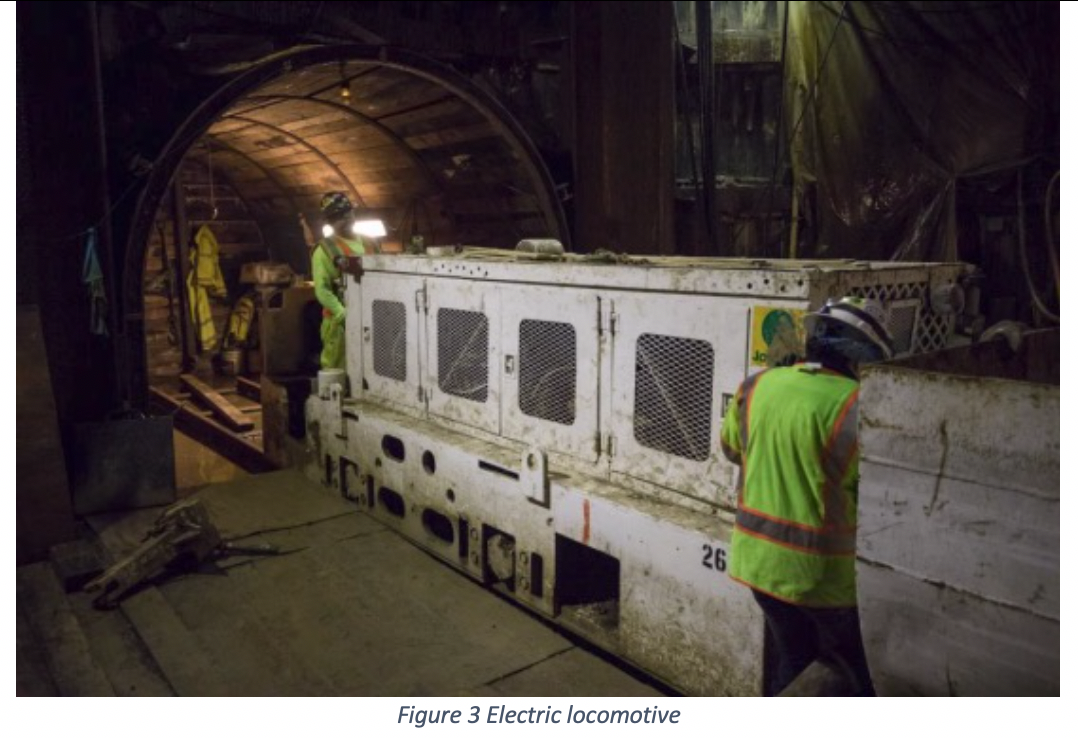

Just as R115’s crew got to the bottom, the patient arrived at their location from three quarters of a mile in the tunnel on a horizontal flat car driven by a battery-powered locomotive (Figure 3).

Captain Horn called for the lowering of the backboard and Stokes basket. The topside crew decided to use the crane again rather than lower with ropes. The county EMS was not included as joint training is not done. Back down at the tunnel, the patient was secured, placed in the 12-man cage, along with R115 members and 2 construction workers. The patient at the top of the shaft was treated by county EMS and was off to the hospital at 09:40 just 38 minutes from the initial call.

There are always lessons learned at any rescue. From prior experience, a member was assigned to the crane operator to ensure that the crane was moved under Fire Department control. The Fire Department used the construction company’s gas detectors because they knew that the detectors were calibrated daily. In retrospect, the Fire Department would use its own gas detectors. Also, the backboard and Stokes basket should have gone down on the first lowering to the tunnel.

The usage of gas monitors had been delayed because of differences in calibration between the fire department monitor and a plant monitor. There is no one gas that is best for calibration of fire department gas detectors because many different exposures are encountered. For a particular industrial site, the explosive gases are most likely known.

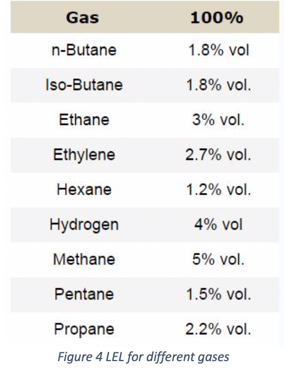

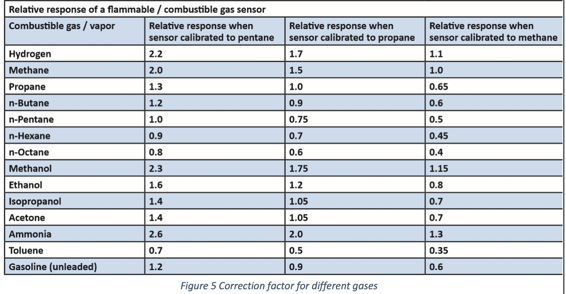

Figure 4 shows that the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) varies according to which hydrocarbon is present. Figure 5 shows correction factors if the monitor is calibrated with one gas and exposed to another. The Fire Department meter was calibrated with methane so that 0.5% by volume of methane reads 10% of LEL. A meter calibrated with pentane has a correction factor of 2 for methane. So, if a meter calibrated with pentane reads 10% LEL in pentane, the meter would read 5% LEL in methane. lf anything, the gas in the tunnel would be methane, but in actuality, the meters read zero no matter what calibration gas was used.

The reason pentane is sometimes used for calibration is that it overestimates the actual LEL. The caveat is that if the meter is poisoned for methane, a methane bump test is indicated. A sensor can be poisoned by chemicals like silicone. Note well, silicone is a component of Armor All which should not be exposed to a LEL meter on a fire truck. The lesson learned here is to understand the effect of different gases on a sensor and a Fire Department may encounter many different gases.

The reason pentane is sometimes used for calibration is that it overestimates the actual LEL. The caveat is that if the meter is poisoned for methane, a methane bump test is indicated. A sensor can be poisoned by chemicals like silicone. Note well, silicone is a component of Armor All which should not be exposed to a LEL meter on a fire truck. The lesson learned here is to understand the effect of different gases on a sensor and a Fire Department may encounter many different gases.

Author Bio:

Skip Williams was a volunteer firefighter for 20 years. His last position was captain of the high-angle rescue team and emergency medical technician. He has a Bachelor of Electrical Engineering from Georgia Tech and M.S. and Ph.D. from Rutgers University and has held teaching positions at Rutgers University and the Medical College of Georgia. He designed and patented an artificial heart assist device. He is a Registered Professional Engineer in New Jersey and is a practicing engineer with Condition Analyzing Corporation engaged in condition monitoring of ships.

Note: Captain Tom Horn is a graduate of two Roco Rescue courses.