In confined space work, ensuring air quality is a top priority. With directives from OSHA and consensus recommendations from ANSI & NFPA, understanding the ins and outs of atmospheric monitoring is key. This article will briefly review what OSHA requires as well as what ANSI, NFPA and Roco recommend for practices that ensure worker safety remains the top priority in working in these challenging environments. While the OSHA General Industry standard allows for periodic monitoring and sets no exact timespan between testing – however, as a safer way, Roco recommends continuous air monitoring any time workers are in the space.

OSHA 1910.146 refers to testing the internal atmosphere before an employee enters the space and testing as necessary to maintain acceptable entry conditions. Testing should be based on the hazard assessment for a given space as well as how rapidly those hazards could cause a change in the atmosphere, which may require additional action for safe entry.

OSHA 1910.146 refers to testing the internal atmosphere before an employee enters the space and testing as necessary to maintain acceptable entry conditions. Testing should be based on the hazard assessment for a given space as well as how rapidly those hazards could cause a change in the atmosphere, which may require additional action for safe entry.

OSHA’s Confined Spaces in Construction (1926-Subpart AA) also references monitoring frequency. It states continuous monitoring is required unless periodic monitoring is sufficient to ensure entry conditions are maintained, or continuous monitoring is not commercially available.

Note: Also take into consideration any previous work activities that may have introduced atmospheric hazards into the space as well as any known history of hazardous atmospheric conditions.

"Roco strongly encourages continuous monitoring while workers are inside a permit-required confined space."

Looking at best practice consensus standards, ANSI Z117 advocates for continuous monitoring in situations when a worker is present in a space where atmospheric conditions have the potential to change.

The national consensus standard, NFPA 350 Guide for Safe Confined Space Entry and Work 2022, also generally refers to “continuous air monitoring” when possible. Here’s a quote from NFPA 350, Section 7.13.1 (www.nfpa.org), Continuous Atmospheric Monitoring, “Atmospheric conditions can change quickly or gradually over time; without continuous atmospheric monitoring, air contaminants may increase, or the oxygen percentage may decrease or increase, creating dangerous confined space atmospheric conditions.” NFPA adds, “Entrants, Attendants, and other personnel may be unaware of changing conditions if the air quality was only initially monitored and determined to be acceptable. The atmosphere within and outside the confined space should be monitored continuously to ensure continued safe working conditions.”

PRE-ENTRY TESTING

Although OSHA does not define a specific timeline to conduct pre-entry monitoring, Roco uses as a guideline that a “baseline test” is to be conducted approximately 30 minutes prior to the entry and then again immediately prior to entry. If ventilation is being used as a control measure for atmospheric hazards, initial atmospheric monitoring should be conducted without ventilation to establish a baseline atmosphere.

A comparison of these readings could indicate that atmospheric changes have occurred inside the space. If a space has been vacated for a period of time, it is recommended that similar baseline testing be repeated. This is critical as it may reveal the presence of previously unrecognized or unanticipated atmospheric hazards.

Again, confined space work is inherently hazardous – and atmospheric hazards are a leading cause of fatalities. Do everything you can to keep your people safe. Don’t let your guard down even for a minute!

Additional Resources:

Frequently Asked Questions: OSHA PRCS Standard Clarification

How much periodic testing is required?

The frequency of testing depends on the nature of the permit space and the results of the initial testing performed under paragraph (c)(5)(ii)(c). The requirement in paragraph (c)(5)(ii)(F) for periodic testing as necessary to ensure the space is maintained within the limits of the acceptable entry conditions is critical. OSHA believes that all permit space atmospheres are dynamic due to variables such as temperature, pressure, physical characteristics of the material posing the atmospheric hazard, variable efficiency of ventilation equipment and air delivery system, etc. The employer will have to determine and document on an individual permit space basis what the frequency of testing will be and under what conditions the verification testing will be done.

What does testing or monitoring "as necessary" mean as required by 1910.146(d)(5)(ii) to decide if the acceptable entry conditions are being maintained?

The standard does not have specific frequency rates because of the performance-oriented nature of the standard and the unique hazards of each permit space. However, there will always be, to some degree, testing or monitoring during entry operations which is reflective of the atmospheric hazard.

Some of the factors that affect frequency are:

* Results of test allowing entry.

* The regularity of entry (daily, weekly, or monthly).

* The uniformity of the permit space (the extent to which the configuration, use, and contents vary).

* The documented history of previous monitoring activities.

* Knowledge of the hazards which affect the permit space as well as the historical experience gained from monitoring results of previous entries.

Knowledge and recorded data gained from successive entries (such as ventilation required to maintain acceptable entry conditions) may be used to document changes in the frequency of monitoring.

Learn More

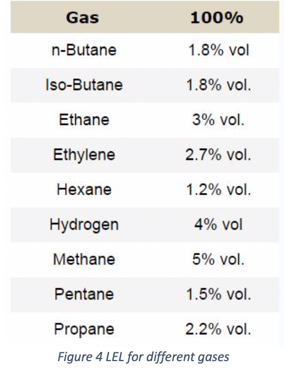

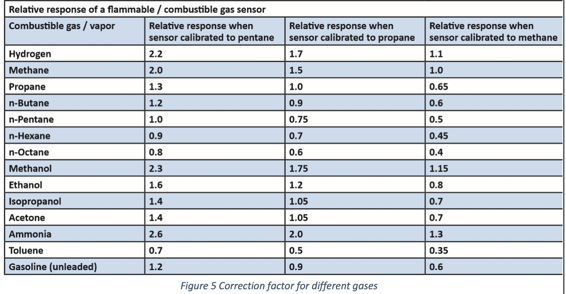

The reason pentane is sometimes used for calibration is that it overestimates the actual LEL. The caveat is that if the meter is poisoned for methane, a methane bump test is indicated.

The reason pentane is sometimes used for calibration is that it overestimates the actual LEL. The caveat is that if the meter is poisoned for methane, a methane bump test is indicated. Our congratulations to the Burlington (Iowa) Fire Department on a successful grain bin rescue that happened in their community back in May of this year (2018). The incident was reported on Firehouse.com.

Our congratulations to the Burlington (Iowa) Fire Department on a successful grain bin rescue that happened in their community back in May of this year (2018). The incident was reported on Firehouse.com. Most often, training programs treat the three functions as separate, independent roles locked into a hierarchy based on the amount of information to be provided. However, it’s critical to note, if any one of these individuals fails to perform his or her function safely or appropriately, the entire system can fail – resulting in property damage, serious injury or even death in a confined space emergency.

Most often, training programs treat the three functions as separate, independent roles locked into a hierarchy based on the amount of information to be provided. However, it’s critical to note, if any one of these individuals fails to perform his or her function safely or appropriately, the entire system can fail – resulting in property damage, serious injury or even death in a confined space emergency. In my opinion, depending exclusively on the Entry Supervisor is faulty on a couple of levels. First of all, the amount of blind trust that is required of that one person. From the viewpoint of an Entrant, do they really have your best interest in mind? And, we all know what happens when we “ass-u-me” anything! Plus, it puts the Entry Supervisor out there on their own with no feedback or support for ensuring that all the bases are covered correctly. There are no checks and balances, and no team approach to ensuring safety.

In my opinion, depending exclusively on the Entry Supervisor is faulty on a couple of levels. First of all, the amount of blind trust that is required of that one person. From the viewpoint of an Entrant, do they really have your best interest in mind? And, we all know what happens when we “ass-u-me” anything! Plus, it puts the Entry Supervisor out there on their own with no feedback or support for ensuring that all the bases are covered correctly. There are no checks and balances, and no team approach to ensuring safety. Many times, we find that the role of Attendant is looked upon as simply a mandated position with few responsibilities. They normally receive the least amount of training and information about the entry. However, the Attendant often serves as the “safety eyes and ears” for the Entry Supervisor, who may have multiple entries occurring at the same time. In reality, the Attendant becomes the “safety monitor” once the Entry Supervisor okays the entry and leaves for other duties. So, there’s no doubt, the better the Attendant understands the hazards, controls, testing and rescue procedures – the safer that entry is going to be!

Many times, we find that the role of Attendant is looked upon as simply a mandated position with few responsibilities. They normally receive the least amount of training and information about the entry. However, the Attendant often serves as the “safety eyes and ears” for the Entry Supervisor, who may have multiple entries occurring at the same time. In reality, the Attendant becomes the “safety monitor” once the Entry Supervisor okays the entry and leaves for other duties. So, there’s no doubt, the better the Attendant understands the hazards, controls, testing and rescue procedures – the safer that entry is going to be! There are countless injuries and deaths across the nation when workers are not taught to recognize the inherent dangers of permit spaces. They are not trained when "not to enter" for their own safety. Many of these tragedies could be averted if workers were taught to recognize the dangers and know when NOT to enter a confined space.

There are countless injuries and deaths across the nation when workers are not taught to recognize the inherent dangers of permit spaces. They are not trained when "not to enter" for their own safety. Many of these tragedies could be averted if workers were taught to recognize the dangers and know when NOT to enter a confined space. The DPW had developed a permit-required confined space program but stopped implementing it in 2004 when the last trained employee retired. They also had purchased a four-gas (oxygen, hydrogen sulfide, carbon monoxide and combustible gases) monitor and a retrieval tripod to be used during the training. It was reported that a permit-required confined space program was never developed because DPW policy “prohibited workers” from entering a manhole. However, the no-entry policy was not enforced. Numerous incidents of workers entering manholes were confirmed by employee interviews.

The DPW had developed a permit-required confined space program but stopped implementing it in 2004 when the last trained employee retired. They also had purchased a four-gas (oxygen, hydrogen sulfide, carbon monoxide and combustible gases) monitor and a retrieval tripod to be used during the training. It was reported that a permit-required confined space program was never developed because DPW policy “prohibited workers” from entering a manhole. However, the no-entry policy was not enforced. Numerous incidents of workers entering manholes were confirmed by employee interviews.