Emergency responders are more likely to develop significant mental health problems than the general population. It is estimated that nearly 30% of first responders will develop depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or even suicidal ideations at some point during their lifetime [1]. Unfortunately, a pervasive stigma surrounding mental health prevents many of these dedicated individuals from seeking help when they need it the most. It’s time to break the stigma and normalize providing help for those who dedicate their lives to helping others.

Rescue workers are exposed to harrowing scenes of devastation, suffering, and loss on a regular basis. Repeated exposure to these critical incidents can impart serious psychological scars throughout the course of even a short-lived career. Some studies suggest that emergency workers are 3 times more likely to develop mental health issues as a result of these exposures [2]. Despite this idea becoming more and more mainstream, emergency workers rarely have an opportunity to process these emotions, and worse, the culture sometimes discourages and chastises this type of vulnerability.

The misguided notion that seeking help is a sign of weakness or an inability to handle the job perpetuates the stigma surrounding mental health in emergency response professions. Consequently, many workers suffer from mental health issues silently, unable to admit they need assistance. This hesitancy to seek help leads to coping with unhealthy habits, placing them at high risk for developing alcohol and substance abuse issues. The reluctance to seek help, combined with these risk factors, can lead to severe and sometimes fatal outcomes.

The misguided notion that seeking help is a sign of weakness or an inability to handle the job perpetuates the stigma surrounding mental health in emergency response professions. Consequently, many workers suffer from mental health issues silently, unable to admit they need assistance. This hesitancy to seek help leads to coping with unhealthy habits, placing them at high risk for developing alcohol and substance abuse issues. The reluctance to seek help, combined with these risk factors, can lead to severe and sometimes fatal outcomes.

The importance of mental health support for rescue workers has never been clearer. Just as they are equipped with the physical tools to perform their duties, rescue workers should be provided with adequate mental health resources which are crucial in safeguarding their emotional wellbeing and overall performance. Early intervention is key, and recognizing signs of mental distress, such as changes in behavior, increased irritability, emotional exhaustion, and social withdrawal, can make a significant difference.

It’s time to break the stigma and normalize providing help for those who dedicate their lives to helping others.

While therapy and counseling are often used as reactive measures, there is a need for proactive programs on the front end. Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) teams are becoming a staple in emergency response agencies. These individuals proactively combat the mental health endemic by helping clinicians deal with stress at its inception. By fostering a culture where seeing help is encouraged and normalized, we can empower emergency response workers to take care of their mental health without fear of judgment.

As emergency responders, we are an integral part of ensuring the safety and health of those in our workplace and communities. While performing this job requires incredible amounts of dedication, courage, and resilience, we must also remember that we are not invincible. By advocating for the normalization of seeking help, we can better support the emotional well-being of rescue professionals and enable them to perform at their best while facing the challenges of their noble profession.

As emergency responders, we are an integral part of ensuring the safety and health of those in our workplace and communities. While performing this job requires incredible amounts of dedication, courage, and resilience, we must also remember that we are not invincible. By advocating for the normalization of seeking help, we can better support the emotional well-being of rescue professionals and enable them to perform at their best while facing the challenges of their noble profession.

[2] https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/733519

The learning takeaway for rescuers is to deepen your knowledge.

The learning takeaway for rescuers is to deepen your knowledge.

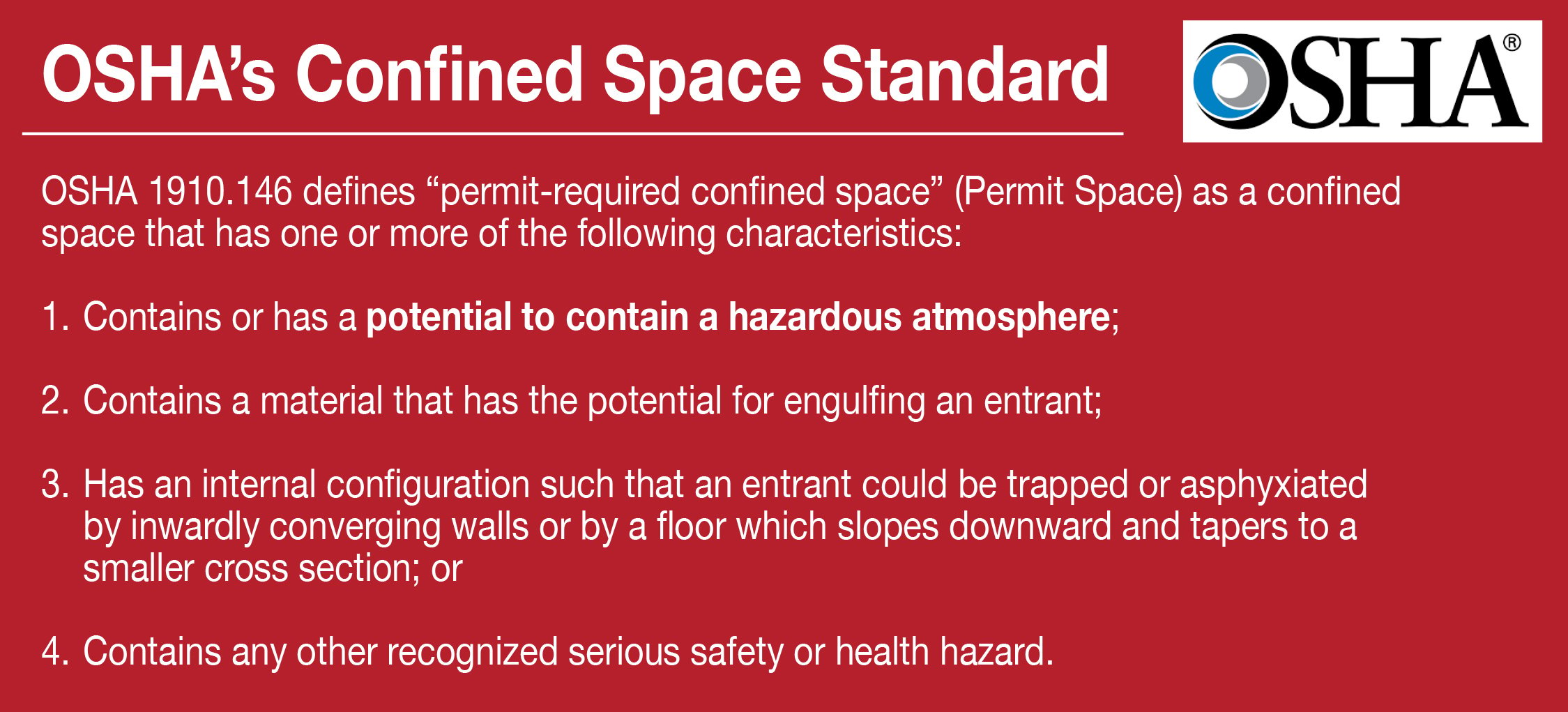

Refineries, plants and manufacturing facilities have a wide range of permit-required confined spaces – some having only a few, while others may have hundreds. Some of these spaces may be relatively open and straightforward while others are congested and complex, or at height. With this in mind, are all your bases covered? Can your rescue team (or service) safely and effectively perform a rescue from these varying types of spaces? Or, are you left exposed? And, how can you be sure?

Refineries, plants and manufacturing facilities have a wide range of permit-required confined spaces – some having only a few, while others may have hundreds. Some of these spaces may be relatively open and straightforward while others are congested and complex, or at height. With this in mind, are all your bases covered? Can your rescue team (or service) safely and effectively perform a rescue from these varying types of spaces? Or, are you left exposed? And, how can you be sure?

Of course, the security of the system's attachment to the crane and the ability to “lock-out” any potential movement are a critical part of the planning process. If powered industrial equipment is to be used as a high-point, it must be treated like any other energized equipment with regard to safety. Personnel would need to follow the Control of Hazardous Energy [Lockout/Tagout 1910.147]. The equipment would need to be properly locked out – (i.e., keys removed, power switch disabled, etc.). You would also need to check the manufacturer’s limitations for use to ensure you are not going outside the approved use of the equipment.

Of course, the security of the system's attachment to the crane and the ability to “lock-out” any potential movement are a critical part of the planning process. If powered industrial equipment is to be used as a high-point, it must be treated like any other energized equipment with regard to safety. Personnel would need to follow the Control of Hazardous Energy [Lockout/Tagout 1910.147]. The equipment would need to be properly locked out – (i.e., keys removed, power switch disabled, etc.). You would also need to check the manufacturer’s limitations for use to ensure you are not going outside the approved use of the equipment. This is where the employer must complete written rescue plans for permit-required confined spaces and for workers-at-height using personal fall arrest systems – or they must ensure that the designated rescue service has done so. When developing rescue plans, it may be determined that there is no other feasible means to provide rescue without increasing the risk to the rescuer(s) and victim(s) other than using a crane to move the human load. These situations would be very rare and would require very thorough documentation. Such documentation may include written descriptions and photos of the area as part of the justification for using a crane in rescue operations.

This is where the employer must complete written rescue plans for permit-required confined spaces and for workers-at-height using personal fall arrest systems – or they must ensure that the designated rescue service has done so. When developing rescue plans, it may be determined that there is no other feasible means to provide rescue without increasing the risk to the rescuer(s) and victim(s) other than using a crane to move the human load. These situations would be very rare and would require very thorough documentation. Such documentation may include written descriptions and photos of the area as part of the justification for using a crane in rescue operations. Of course, one of the most important considerations in using any type of mechanical device is its strength and ability (or inability) to “feel the load.” If the load becomes hung up on an obstacle while movement is underway, serious injury to the victim or an overpowering of system components can happen almost instantly. No matter how much experience a crane operator has, when dealing with human loads, there is no way he can feel if the load becomes entangled. And, most likely, he will not be able to stop before injury or damage occurs.

Of course, one of the most important considerations in using any type of mechanical device is its strength and ability (or inability) to “feel the load.” If the load becomes hung up on an obstacle while movement is underway, serious injury to the victim or an overpowering of system components can happen almost instantly. No matter how much experience a crane operator has, when dealing with human loads, there is no way he can feel if the load becomes entangled. And, most likely, he will not be able to stop before injury or damage occurs.